There was one more great story that came out of Copenhagen. My hosts Kim and Namiko work with a guy called Stanley who is an old-school third-generation molecular microbiologist…third generation meaning that he did his postdoc with a guy named Jon Beckwith, who himself studied with Jacob and Monod in Paris, who are of course first-generation, from the French romantic school of molecular microbiology of the mid 20th century, when molecular genetics were being discovered. I never appreciated the strength of the intellectual principles of molecular microbiology until relatively recently, when I started associating with people like Stanley, Tom Silhavy (also trained with Beckwith, who we’ll come back to shortly), Stephen Trent, Roy Curtiss and the like. They bear a body of knowledge and witchcraft that you can only know by committing to it, and thereby also accepting a scientific value system with respect to how microbiology ought to be approached and of course the sanctity of the gene (which almost everyone abides by these days). Important bodies of scientific knowledge necessarily come with a partially contrived set of methods and vocabulary, and gatekeepers. But it’s a fair trade, in some sense, because along with that value system you do inherit a deep and detailed practical understanding of…the trade. I don’t pretend to be a member of the club, but I like to listen to them talk, with wide eyes.

Stanley inherited the old-school style: he studies the fine-scale genetics of bacteriophage lambda, using the classic methods to correlate genotype with phenotype. I wish I could remember all the details of what he studies and how he does it, and more importantly, I wish I could remember all the knowledge he dropped on me about the history of E. coli strains and why we study the strains we do. But there is one thing he told me that i’ll never forget…

Jon Beckwith, 2nd generation molecular microbiologist, professor at Harvard Medical School to this day, is famous for many reasons but perhaps the most poignant scientific reason is that his research group was the first to isolate a gene. As Stanley told me, they isolated the lac operon, that is, double stranded DNA from E. coli that encoded the lac operon, which is a set of genes that metabolizes lactose and is the best studied set of genes in biology. Stanley explained to me the biochemical details of how they did it, which you can also read in Jon Beckwith’s acceptance speech for the Eli Lilly award, which I’ll come back to in a second. But first it’s worth marinating on Jon and his colleagues’ reaction to their achievement. The New York Times published a short article called “Playing with Biological Fire” in which Beckwith described their own achievement as “frightening,” and in a piece by the Harvard Gazette, one of the graduate students on the paper said that “The only reason the news was released to the press was to emphasize its [the science’s] negative aspects. We did this work for scientific reasons. It was fun to do – cute tricks and all that. But the more we think about it, the consequences of our work seem frightening rather than beneficial.” That makes me laugh every time I read it. It’s very rare to hear scientists discuss their own work in such a negative, or at best skeptical, light. I don’t know if it was different back then, if self-promotion wasn’t considered as essential career-wise. I suppose it was the same though. It may have been the magnitude of the discovery that allowed them to react like this. It might have even been because of its magnitude that they had to react like this: they could at once lean on the historic nature of the work while simultaneously exonerating themselves from its future consequences by criticizing it. It seems like we see a somewhat similar reaction with the development of CRISPR-Cas based gene-editing. However, with CRISPR, most of the leading figures are ferociously trying to commercialize it while simultaneously warning of the perils of gene-editing; that doesn’t appear to have been the case with Beckwith and company.

There is a very deep conviction within science that ‘it is good.’ This is not explicitly told to science students, but it is strongly instilled implicitly in many ways. In biology, for example, most talks and grants include some mention of relevance to mitigating disease. In fact, science is neither better nor worse than society as a whole, because it is part of society. Science saves peoples’ lives and it kills people. It cleans the environment and it pollutes it. It enables wars…does it broker peace? Just as all citizens are in some sense responsible for the dysfunctions and immoralities of their society, all scientists are responsible for those of the institution of science. In society, there are various ways to undermine societal immoralities: voting, philanthropy, activism, etc. In science, we’re often encouraged to ‘promote science,’ as a form of social outreach, as if science and rational thinking were purely good endeavors that only counteract non-scientific societal immoralities, but we’re rarely asked to try to undermine the immoralities of science itself.

Jon Beckwith appears to be cut from a different cloth. He wasn’t just critical of his own achievements, but of science. The acceptance speeches for major scientific awards like the Eli Lilly award (or the Nobel Prize) are typically narrative descriptions of the discoveries that led to the award, and so is the first half of Beckwith’s Speech. But in the second half, he not only criticizes science, he also criticizes drug companies like the Eli Lilly company who gave him the award. Stanley sent me a transcription of the speech – here are some highlights:

“It is almost trite now to go over the ways in which science has contributed to many of the ills that we and nations all over the world are facing. It’s enough to pick up the newspaper almost any morning and think about how many of the problems being discussed derive more or less directly from work that we scientists are doing or have done.”

“I have given some talks and participated in discussions with various groups in which I, along with others, tried to point out the misuses of science by our government and by industries in this country. One of the examples I have consistently used is the role of the drug companies. Oddly enough, it wasn’t until very recently that I saw any contradiction in accepting an award donated by a drug company and speaking on these issues on other occasions.”

“What I am trying to say is that science in the hands of the people who rule this country and who run our industries is being used to exploit and oppress people all over the world and in this country.”

And finally, for the most mind-blowing part of the speech (given in 1969 mind you):

“In a just society, those who received the awards should be those who are contributing in a meaningful way to the welfare of all people. In that light, I consider that the Black Panther Party is an organization which is so contributing. They are not only helping their own people to lose their feeling of powerlessness, but are also setting up free health clinics and free breakfast programs in their communities, which could be models for the type of society we would like to see. They also recognize that it is the system of capitalist exploitation which is an essential component of the way in which our society oppresses people. Our society has rewarded them with the worst example of repression seen in this country in recent years. Therefore, after consultation with my colleagues, who have contributed to the work for which I am receiving the prize, we have decided to donate one half of the prize money to the Boston Panther Free Health Movement and the other half to the Defense Fund for the Panther 21 in New York.”

It doesn’t get any better than that.

A few weeks after Copenhagen I attended a prison abolition conference at Princeton where a mix of activists and scholars spoke about how effed up the carceral state is. It was held in an antique wooden church-like auditorium almost celestial with spring light streaming in from above giant windows above the stage. I sat down with my coffee and there was an old black man, with black vest, black hat, and a couple chains around his neck, sitting behind me, on his laptop, and he would emit loud “mm-hmm”‘s whenever one of the panelists would say something about the carceral state that he particularly agreed with. Later on in the day there were various workshops that you could choose between and I decided to go to the one called “Organizing with the Black Panthers,” maybe because Beckwith’s speech was still speaking to me. It was the old guy who had sat behind me and his friend, who were black panther old-timers, and who mostly talked about political prisoners in the U.S. and told stories about the old days. They also showed some Youtube videos, interviews of exonerated political prisoners like Alfred Woodfox. They couldn’t figure out some AV issue so like Johnny on the spot I swooped in and figured it out. The guy: “My maan…” During the Q&A no one asked any questions so I asked them “was there any formal organization between the Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam?” Just curious. “We had some panthers who were in the Nation, yes, and some of them came over to us.” But not much, I gathered.

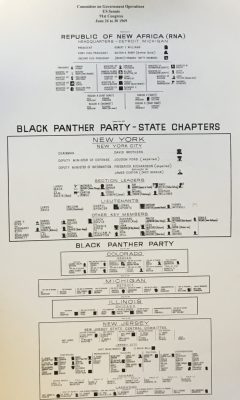

At the end of the day, the two guys had set up a card table with some merch: t-shirts, hats, etc. When i walked by a small poster for sale caught my eye. It was a print of an exhibit to Congress from 1969 detailing the structures of black organizations in the United States. The poster caught my eye for two reasons: first, it showed the leadership of the Colorado Black Panther Party. Second, besides that of the Black Panther Party, it showed the leadership of another organization. I didn’t know about, The Republic of New Africa, whose Second Vice President was Betty Shabazz (Malcom X’s widow) and whose Minister of Culture was Leroi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka). The RNA: Congress was presented with its structure, but not its function. Jon Beckwith knew its function.